christmas is kind of like if for 1/6 of the year everyone got really into ska and started wearing the fedoras and checkered clothing and they only played ska music in stores that the employees clearly weren’t enjoying and everything was just ska themed for a while and one day someone eagerly asks you what ska you’re listening to and when you tell them you’re not doing the whole ska thing for the tenth time in a row its like a 50/50 chance that their face suddenly falls deathly serious and they say “are you one of those people who thinks all orphans should be drowned in boiling shit?” or they chuckle and squint at you and say “oh yeah you must be one of those people that listens to pop punk! Its kinda like a weird, different ska I guess! I am going to a ska concert later today if you wanna come along and see how awesome ska is, as enforced by the ephemeral force of enjoying ska instilled in all moral beings!” and this has been going on for so long that all the ska music is just people saying “pick it up” over and over again and plastering everything in checker patterns and theres a whole wave of people who think everyone has forgotten how to really enjoy ska but they actually just want an older version of the artificially enforced ska mania everyone is having and they made a book and several movies called “the man who did not like ska” about a disgusting evil spinach creature that hated everything and ate broken glass every day who learns basic empathy after hearing an upstrummed guitar for the first time.

I’ve been meaning to write about this interesting essay by Michael Green, about how the poverty line could be pegged at $140,000 per year, if we’re talking about what he calls “the cost of participation” in contemporary American life.

Some of the claims in the essay are hyperbolic, and it was largely derided by the green eyeshade battalions of the dismal science, but it nevertheless struck a nerve for good reasons. For example:

Critics will immediately argue that I’m cherry-picking expensive cities. They will say $136,500 is a number for San Francisco or Manhattan, not “Real America.”

So let’s look at “Real America.”

The model above allocates $23,267 per year for housing. That breaks down to $1,938 per month. This is the number that serious economists use to tell you that you’re doing fine.

In my last piece, Are You An American?, I analyzed a modest “starter home” which turned out to be in Caldwell, New Jersey—the kind of place a Teamster could afford in 1955. I went to Zillow to see what it costs to live in that same town if you don’t have a down payment and are forced to rent.

There are exactly seven 2-bedroom+ units available in the entire town. The cheapest one rents for $2,715 per month.

That’s a $777 monthly gap between the model and reality. That’s $9,300 a year in post-tax money. To cover that gap, you need to earn an additional $12,000 to $13,000 in gross salary.

So when I say the real poverty line is $140,000, I’m being conservative. I’m using optimistic, national-average housing assumptions. If we plug in the actual cost of living in the zip codes where the jobs are—where rent is $2,700, not $1,900—the threshold pushes past $160,000.

The market isn’t just expensive; it’s broken. Seven units available in a town of thousands? That isn’t a market. That’s a shortage masquerading as an auction.

And that $2,715 rent check buys you zero equity. In the 1950s, the monthly housing cost was a forced savings account that built generational wealth. Today, it’s a subscription fee for a roof. You are paying a premium to stand still.

Green emphasizes that for couples with young children, childcare costs are a devastating addition to household budget. For many people in their 20s and 30s, this means “choosing” to be childless, because it feels fundamentally unaffordable. This of course helps explain why the birth rate has been cratering for decades — it’s now quite literally half of what it was when I was born at the peak of the baby boom. And the birth rate in the US is still a lot higher than in much of the developed world, The worst situation, not surprisingly, is in countries that still have strongly patriarchal traditional cultures, i.e., women are expected to do all childcare and other domestic labor, but where women also now have a certain degree of economic and social freedom. In places like South Korea, the consequence of that combination is a total fertility rate of less than one — a completely unprecedented situation in all of recorded history, and no doubt in the entire history of the species, or otherwise we wouldn’t be here to blog about it.

The Times had a piece today (gift link) that used Green’s essay as a jumping off point. The basic economic problems here are well known: the cost of housing, of childcare, of health care, and of higher education. These things are all central to any concept of a middle class lifestyle. Of course another big factor in all this are changing standards of what’s considered an acceptable version of such a lifestyle:

Mr. Thurston, from Philadelphia, said he wanted children. But right now, he and his partner must climb three floors to their rental apartment. Their car is a two-door “death trap.”

His salary, about $90,000, would need to cover student loans and child care. He also wants to live in a good school district and pay for extras, like music lessons and sports leagues.

“I know you don’t need those things,” he said, “but as a parent, my job is to set my child up for success.”

Even for those who own a home, the thought of children can be daunting. Stephen Vincent, 30, and his partner, Brittany Robenault, a lab technician, first went to community college to save money. Then, he said, they “ate beans and rice” for several years to save for a down payment.

Now an analyst for a chemical company with a household income of about $150,000, he likes his lifestyle in Hamburg, Pa., and wants to keep it.

“We live in the richest country in the history of human civilization, so why can’t I eat out twice a week and have kids?” he said.

To the skeptics who say these trade-offs are simply lifestyle choices, there was a rejoinder: Hey, you try it.

“It’s very easy from a place of wealth and privilege to say, ‘You should be happy with something more modest,’” Mr. Thurston said.

But, he said, “it would kind of suck to live that way.”

Alicia Wrigley is grappling with the trade-offs. Ms. Wrigley and her husband, Richard Gailey, both musicians and teachers, own a two-bedroom bungalow in Salt Lake City and feel lucky to have it — they say they could not afford it now. But juggling in-home music lessons with their 2-year-old’s needs can feel like a squeeze. They want another child, but wonder how it would all work.

“I know it’s possible,” she said, looking through the window at her next-door neighbor’s house, which is exactly the same size.

That neighbor raised six children there in the 1970s. One way mothers then would cope, Ms. Wrigley said, was to “turn their kids out all day, and they’d just run around the neighborhood.”

She said she would not do that today, not least because someone might report her.

“The world,” she said, “is fundamentally different now.”

This is reminds me obliquely of a passage in The Road to Wigan Pier, Orwell’s study of life in a mining town in northern England in the mid-1930s. Orwell is interviewing a family of eight living in a four-room house (I would guess this would probably be in the neighborhood of 800 square feet or so), and he asks them when they became aware of the housing crisis. “When we were told of it,” is the reply.

. . . commenter Felix D’s question about this passage led me to look it up, and it’s somewhat different than I recalled, but the gist is the same:

Talking once with a miner I asked him when the housing shortage first became acute in his district; he answered, 'When we were told about it', meaning that till recently people's standards were so low that they took almost any degree of overcrowding for granted. He added that when he was a child his family had slept eleven in a room and thought nothing of it, and that later, when he was grown-up, he and his wife had lived in one of the old-style back to back houses in which you not only had to walk a couple of hundred yards to the lavatory but often had to wait in a queue when you got there, the lavatory being shared by thirty-six people. And when his wife was sick with the illness that killed her, she still had to make that two hundred yards' journey to the lavatory. This, he said, was the kind of thing people would put up with 'till they were told about it'.

The post The affordability crisis appeared first on Lawyers, Guns & Money.

4. Start miming. Just do a whole performance as a mime stuck in a box. Then ask "can AI do THAT?"

The post Things To Do When Your Family Tries To Talk To You About AI This Holiday Season appeared first on Autostraddle.

Laura Wellington is estranged from one of her adult daughters. The Connecticut 59-year-old is somewhat famous for this, in fact, or anyway famous for her response to it. Across Tiktok and Instagram, under the name "Doormat Mom," Wellington's railing against the supposed injustice done to her by a daughter she calls an "ungrateful little bastard" has brought her some 140,000 total followers. This past weekend she was one of the subjects of a Wall Street Journal article reporting on what the writer Elizabeth Bernstein calls a "movement" aiming to "reduce stigma, build community, and empower others who are enduring one of life's most painful experiences: the loss of a child who is still alive."

From the Journal article, a reader can learn that Wellington, who regards herself as a good mom, reportedly initiated the estrangement herself, after learning she wouldn't be invited to her daughter's wedding. You can learn that Wellington, in addition to her dedicated Tiktok and Instagram accounts, also has launched Facebook and YouTube accounts, a podcast, and a self-published book, all themed around the supposed phenomenon of parents being unjustly cut off by their cruel adult children. You can certainly, on the basis of these facts, start to form a pretty good idea of what kind of person Laura Wellington is, and, say, what it might be like to encounter her as a worker in a retail or customer service job.

What's the opposite of a lazy person? Whatever it is, I can't call myself that. I won't self-deprecate so I don't call myself lazy, either. But if there's a spectrum, I'm closer to lounge-on-the-couch than organize-a-5K. As a small-business owner, I'm always looking for ways to supercharge my work. Most of my clients don't have endless supplies of cash. I try to deliver as much as I can within their budget. What's more, I can't be an expert on everything. I will always have a few things I have to outsource to someone who is more knowledgeable than me. So when the hype of AI hit the consulting world, it should've been an easy decision for me to jump on board. Instead, I watched with a mix of curiosity and horror as it burrowed into every part of the american economy.

Rachel Kacenjar at Work in Progress Consulting saw this wave coming. Back in September, Work in Progress published an AI Policy for their work. Even a few months ago I wasn't sure I needed a policy for my business. I thought I could skate past AI like I had other fads: NFTs, Labubus (Labubi?), and blockchains. Harvard economist Jason Furman making news recently changed that for me. He calculated that 92% of GDP growth in america in the first half of 2025 was due to AI investments. No matter what happens to it in the future, that much money doesn't evaporate overnight. Except for NFTs—wow, what a tumble they had, huh?

I set out to write my own AI policy. I realized that I only really knew the edges of what I was trying to achieve. Would a blanket policy work for all the ways that AI is infiltrating our lives? Would clients care about the stance that I took against it? If AI reached a critical mass with my consultant colleagues, could I afford to be in open rebellion against it? As in everything I try to do, before I could take a stand on AI, I needed to seek to understand it.

@talentagencyguide Ethan Hawke says that he's "bored by Al," saying he prefers real human connection. He calls Al a "plagiarizing mechanism" and jokes that while he knows it's changing the world, he's in "open rebellion" against it. #ai #acting #theatre #actor #actress ♬ original sound - talentagencyguide

what is AI?

I knew before I started working on this essay that "AI" is not one thing. There's a lot of hype out there that takes advantage of this. The AI that people are using today is not the same version that executives sell to shareholders. Even within the umbrella of real-world AI lies many different models and functions. I created the summary below with guides from IBM and Sully Perella from Schellman.

Narrow or Weak AI. This is the type of AI we have now. Every type of AI that exists today fits within this broad category. This type of AI can perform tasks that someone asks it to. Someone has to write the instructions beforehand. Weak AI can't do new tasks based on what it already knows. Reactive Machine AI can perform the same task over and over but can't learn from what it's done. One example of Reactive Machine AI is Deep Blue, IBM’s chess-playing program. It can calculate the most probable chess move out of millions of options, but it is terrible at Jeopardy. (It was IBM’s Watson that played Jeopardy). Limited Memory AI can remember things it has said or done. Google's Gemini AI can hold on to conversation details for a while before forgetting them. It was also pretty full of self-loathing (relatable) before a software update fixed that (unrelatable).

Strong AI or Artificial General Intelligence (AGI). This type of AI doesn't exist, but everyone with money wishes it did. This AI can go beyond Narrow AI to complete tasks that nobody programmed it to do. It learns and responds to stimuli; modifies its own code, more or less. Over time, it could have about the same cognition as a human.

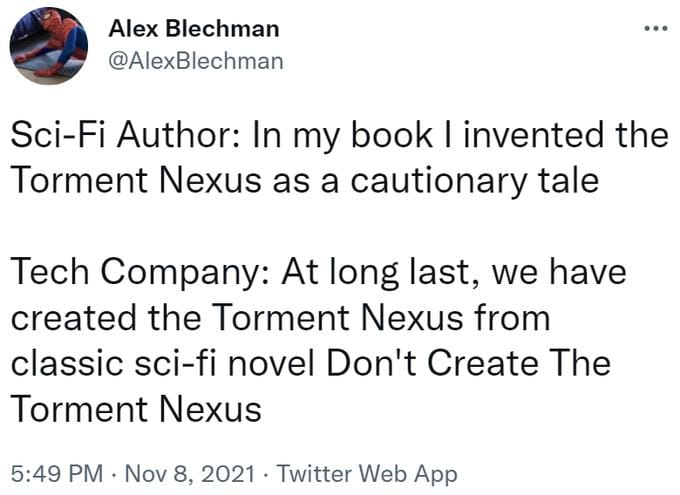

Super AI. This is about as science fiction as we can get. Super AI combines human reasoning with lightning-fast processing time. It can learn, respond, and direct itself to do things based on what it learns. This is basically Skynet if you're a Terminator fan. It's the kind of dream for anyone who would get excited by a torment nexus.

everything people use today is Narrow AI

Within the umbrella of Weak AI is all the AI that we use today. But these distinctions are important to understanding the AI that’s around us.

Machine Learning. This is a type of AI trained to identify patterns in the data it receives. For most Machine Learning AI, it can learn over time the patterns that are legitimate and the ones that are not. My favorite example is the AI that can detect cancer tissue in scans earlier than humans can (more on that later).

Large Language Models (LLMs). This is a form of Machine Learning. Its speciality is interpreting and generating text. ChatGPT is the most famous example of an LLM. Its purpose is to mimic human speech and respond to what people say to it. It can translate languages and carry on a conversation. Others are the chatbots on every website and the autocomplete in emails and texts are LLMs. An LLM is what summarizes product reviews or scans PDFs without you needing it to. And the LLM Google Gemini is famous for suggesting that you glue your toppings to your pizza.

Generative AI (gen AI). This is the famous sibling, to be honest. Generative AI creates new images based on art and images it has scanned. It can create music based on styles and genres it trained on. And it can create new code based on the libraries of code it can already access. But it can’t invent new code and it doesn’t know how well it does at something. Sully Perella writes that this AI would learn how to be a chef by "reading books with favorite recipes.”

When people talk or write about AI today, it's likely that they mean one of these types. I find it important to know the difference between types of AI, what each can do, and what people are saying it can do. Now that I’ve parsed the differences in AI that I know of, I’ll share my misgivings with it.

AI is bad for the environment

Every form of AI today has similar environmental impacts. With every query, AI is running thousands of lines of code. AI software "lives" in data centers that house its programming. These data centers use a lot of energy to process these queries. It takes a lot of water to cool to processors so they don't overheat. This is draining the water supply in areas that don't have much to spare. Data centers have to choose between cooling with water and cooling with air conditioning. That makes their energy usage even worse. Michael Copley at NPR reports that one AI data center can use as much electricity as 100K households. Data centers now under construction will need the same amount of power as 2M households.

Data centers house more programs and services than AI alone. We've relied on them since the Internet exploded in the 1990s. But AI is driving a data center boom. AI-peddling companies need to build up a supply of processing power for the AI of the future. It's this future AI that is driving growth and investments. Power-hungry data centers keep cities from retiring their coal-burning power plants. It's behind the reopening of the Three Mile Island nuclear plant (the one that had a partial meltdown in 1979).

AI is racist

We already know enough about the environmental impacts of AI. Like everything else, Black and brown communities feel that harm the most. But the impact of AI on BIPOC communities goes beyond pollution.

Large Language Models amplify the biases that their creators instill in them. Grok, another model, calling itself MechaHitler is an extreme example of this. But jokes about robot Nazis at a company led by a human one can hide larger issues at stake.

Covert racism touches everything. It's what leads white people to quote MLK, Jr. while avoiding "sketchy" neighborhoods. Unfortunately, AI has inherited the biases of the society that built them. Hofmann, Kalluri, Jurafsky, and King studied the covert racism of LLMs. These LLMs treat people worse when they speak in African-American English (AAE) dialect. The authors found that AI depicted these users as, “more criminal, more working class, less educated, less comprehensible and less trustworthy when they used AAE rather than Standardized American English (SAE).” They asked 5 popular LLMs to pass sentencing decisions on hypothetical alleged murderers. The "defendants" submitted a statement to each LLM written with either AAE or SAE. Each model gave AAE-using defendants harsher sentences than people who spoke SAE. What's more, AI is more likely to mistranscribe or misunderstand AAE speakers. My own experience with the AI transcriber otter.ai backs this up. It struggles to transcribe the non-white names it hears, even when we spell names the same way they sound.

LLMs work by training on work that someone has already written. Chances are, that source material holds racial biases the AI then amplifies. The study authors write:

“we found substantial evidence for the existence of covert racio-linguistic stereotypes in language models. Our experiments show that these stereotypes are similar to the archaic human stereotypes about African Americans that existed before the civil rights movement, are even more negative than the most negative experimentally recorded human stereotypes about African Americans, and are both qualitatively and quantitatively different from the previously reported overt racial stereotypes in language models, indicating that they are a fundamentally different kind of bias. Finally, our analyses demonstrate that the detected stereotypes are inherently linked to AAE and its linguistic features.”

It's unfortunate that AI is somehow more biased than biased humans. But this AI is in software that's already in front of the public. It's integrated into features and decisions that are already in use. Even Machine Learning can be racist. Police arrested Robert Williams because of face recognition technology that falsely identified him. ICE now uses facial recognition software to decide if people on the street are citizens.

AI used in healthcare also shows significant bias. Insurance companies use algorithms to determine who should receive complex care. They wrote the algorithm to rank patients higher if the costs for their care were higher. But researchers found that Black patients were much sicker by the time they got complex care. Because Black patients spend less on healthcare, the algorithm didn't rank them high. Because of this, Black patients received complex care less often than white patients.

The problem in all these cases is not that AI is racist and humans are not. Instead, it's that AI is automatic and harder to correct. Most of us can't see or understand the code that makes up AI. We have to trust that coders will set aside the biases and prejudice they may not even know they have.

AI is dumb and it makes us dumber

The power of decisions is another factor in the capabilities of AI. Sci-fi author Ted Chiang wrote about decisions being at the very heart of good (and by extension, bad) art.

He writes that art is about creation, and the act of creation is about making decisions. A novel or painting is the result of many decisions. What will this tree look like when we're done with it? How will this character's story arc twist in creative ways? How do we present something to audiences that is both familiar and alien? Every work of art is a collection of these decisions. An AI is capable of mimicking that. But AI itself doesn't know whether what it creates is art. It takes us, our human minds, to find meaning in that art and decide if it's worthwhile.

But by that definition, generative AI can create art with input from a human user. Chiang tells the story of film director Bennet Miller. Miller created gallery-worthy art using the gen AI program called Dall-E 2. He would write descriptive prompts and view what Dall-E 2 geneated. He would then input more prompts to tweak the art until it satisfied him. But the 20 pieces of Dall-E 2 art he exhibited took more than 100K images to create. As Chiang writes, Miller's experience is one that OpenAI and other companies want us to have. But they can't sell the fact that it could take thousands of tries to create something worth having. They depict their software as easy to use, creating blockbusters with just a few prompts. But Chiang believes that even as a tool for artists, generative AI makes a whole lot of chaff for scant wheat. “The selling point of generative A.I. is that these programs generate vastly more than you put into them, and that is precisely what prevents them from being effective tools for artists.”

I fear that AI is doing more than making dumb art. It's making us dumber, too. When AI summarizes articles or books, it saves us the time by reading the whole thing. Reading a book isn't about the rote receipt of information. We can't even trust the information: AI makes up details and events that never happened. AI companies say they'll never be able to fix the problem of AI hallucination. LLMs and generative AI will always get facts wrong.

the risks of discernment

When we use AI to create something for us, we become the editors. I recently interviewed for a contract grant writer role with a small non-profit. With confidence, I assured the executive director that I would never use AI in my work with them. "Oh, you're right, I never use it," she replied. "Well, I have AI write all my emails, but then I tweak it to sound better." AI shifts our role away from imagination and decisons-making and closer to discernment. What makes something feel well-written to us? Is editing an essay made by autocomplete much different than writing it ourselves? LLMs take a prompt and create the most probable string of words as its answer. It can't make a turn of phrase except by accident. And it isn't creating new works of art as much as it is blending many sources of art. Generative AI doesn't create millions of ideas and chooses the one it likes the best. We have to do that.

How is this different from having an employee you assign tasks to? When I ask a human to do something, they are using their experience and knowledge to make decisions. I can give them feedback and they'll improve upon it. They might even improve on my work or take it in a direction I didn't expect. AI can mimic this, but it will never come up with something it hasn't seen already.

When we do use AI, there is some proof that it makes us worse at our jobs. Computer scientists using AI believed that it made them 20% faster than if they worked without it. Instead, they were spending 19% more time on a project with the help of AI. Paul Hsieh at Forbes wrote about another recent study published in the Lancet. They measured physicians' ability to detect polyps in a colonoscopy. When the doctors used AI, they detected slightly more polyps than doctors who weren't using it. But the difference between groups was slim: a less than 0.5% improvement. What's interesting is what happened after the physicians had gotten used to using AI. Physicians using AI that stopped using it suddenly got worse at detecting polyps. The study authors write, “continuous exposure to decision support systems such as AI might lead to the natural human tendency to over-rely on their recommendations.” While AI support might get better over time, we might be worse off if we ever choose not to use it.

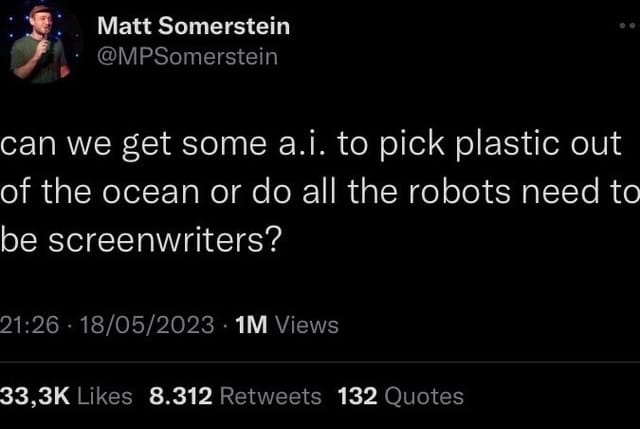

AI will take our jobs (and it will be bad at them)

My theory is that AI is a long-term project to limit or even end the human workforce under the guise of saving money. Thousands of people have already lost their jobs to some form of AI. One expert believes that right now AI could replace less than a third of the workforce. But the level of investment in AI is so high that I can't imagine companies would be willing to stop there. The american economy boomed during the 400+ years of Black enslavement and exploitation. Free land plus free labor drove the engine of our economy for centuries. Incarcerated laborers fill shelves with goods they make in american sweatshops. What if those manufacturers could give their shareholders a better quarter? What if they could push their labor costs closer and closer to zero? Wouldn't they claim it was their duty to do so? Is any human life worth more than a shareholder's dividend?

Bookstore giant Powell's in Portland, OR came under fire for putting AI art on their store merch. Powell's apologized after the AI slop hit the news. But the employees' union gave a statement that clarified Powell's knew all along. "If Powell’s leadership is truly ‘committed to keeping Powell’s designs rooted in creativity and imagination,’ we hope in the future they will be more receptive to feedback from their many creative and imaginative employees—among them, an enormously talented in-house design team." Portland is a city full of artists. I always find a mural, graffiti, or other art to admire when I'm there. Even when those artists work for Powell's, executives still prefer a non-human touch. If that's not a world we want to live in, we need to say so.

I'm better than AI

My mind has spent a lot of time on that concept of discernment. As a consultant, creativity is my bread and butter. I make a lot of decisions in my daily work: how to design a project; how to guide a focus group I lead; how to pivot in a workshop. How is that different from rewriting an AI-drafted email? Or having an LLM give me a list of icebreakers to choose from? One could argue that the difference is so small that most people won't notice.

In the two weeks it took me to write this, a startup announced it invented the world's first AGI-capable model. Nobody knows whether this is true, but it's likely that that day will come sometime in the future. Will the AGI be more capable than us? Will autonomous AGI or Super AGI robots take over our homes? For now, I see AI as a tool—one that may have real benefits, but not at the level of ubiquity it now enjoys.

I was talking with a colleague about AI policies several weeks ago now. "It's pointless to write one," she said. "AI is changing so fast that as soon as you do it'll be obsolete." She may be right. I'm still planning to write one—by hand. I know what a unique experience it is to be human. I'm not ready to give that up yet.

I will share be the future/Future Emergent's AI Policy in a January blog post.