RoboCop: A Glorious, Scathing Satire of America

Published on January 28, 2026

Credit: Orion Pictures / MGM Studios

Credit: Orion Pictures / MGM Studios

RoboCop (1987) Directed by Paul Verhoeven. Written by Edward Neumeier and Michael Miner. Starring Peter Weller, Nancy Allen, Ronny Cox, Miguel Ferrer, and Kurtwood Smith.

Let me start with my favorite story about the making of RoboCop.

In the middle of the 1980s, film producer Jon Davison, then working at Orion Studios, picked up a screenplay by two young screenwriters. Davison is the man who produced the films Airplane! (1980) and Top Secret! (1984), those gleefully over-the-top parodies that people of a certain generation (i.e., me and my siblings) still reference incessantly. Davison liked the satirical nature of this script that was titled RoboCop: The Future of Law Enforcement. At first, he and the studio intended Jonathan Kaplan to direct it. When the director he had in mind left to work on a different movie, Davison had to find another.

That proved to be rather difficult. The studio approached David Cronenberg (who, as far as I can tell, was offered every sci fi movie produced in the ’80s) and Alex Cox (director of Repo Man [1984]), but they both turned it down, and nobody else the studio considered was able to sign on. They started to think the movie would never get made.

Finally, one of the people at Orion, Barbara Boyle, suggested they send the script to Dutch director Paul Verhoeven, with whom the studio had recently worked with on his first English-language film. The grim, gory historical Flesh and Blood (1985) had been a resolute failure, the kind of box-office bomb that makes a movie vanish from theaters almost as soon as it arrives. Screenwriter Michael Miner would later say, “[Edward Neumeier] and I were two of only a handful of people in the theater when we went to see it.” They, and everybody else, were more impressed by Verhoeven’s 1977 war film Soldier of Orange. The studio sent Neumeier and Miner’s screenplay to Verhoeven to see if he was interested.

Verhoeven read maybe one page of the script and threw it away. “I thought it was a piece of shit,” he would later say.

It was his wife, Martine Tours, who read through the script and persuaded him to reconsider. He listened to her, but he’s always been very frank about the fact that he didn’t get it at first. He didn’t understand the humor. He didn’t understand the satire. The title was too cheesy. The story was too American.

I love this bit of backstory for a couple of reasons. One small reason is that it’s hilarious to imagine Verhoeven chucking the screenplay away in disgust, not knowing that RoboCop would one day become his career-defining magnum opus.

The larger reason is about what happened next, which is that Verhoeven actually read the screenplay to figure out what he was missing. He looked for the character hooks his wife had seen. He asked Neumeier and Miner to explain the politics, the satire, the humor. He didn’t understand why they wanted the movie to be darkly funny instead of serious, so Neumeier gave him a pile of comic books, including Judge Dredd; Verhoeven dutifully read through them to understand out what tone the screenwriters were going for.

In a 2017 interview, Miner said, “Ed and I were the luckiest screenwriters in the decade of the ’80s.”

He’s got a point. It’s more or less taken as fact in the film industry that the screenwriter stops mattering once a director signs on to a project, and the film that gets made will be a reflection of the director’s vision. It’s vanishingly rare to hear about a director putting so much effort into crafting a film that is exactly what the screenwriters want it to be.

I also feel like if we surveyed people, just in general, and asked them to name movies that are screenwriter-driven rather than director-driven, most would probably come up with serious, dialogue-heavy dramas. Most would probably not name an ultraviolent ’80s sci fi satire that features a man’s skin gruesomely melting off after he crashes into a giant tank helpfully labeled “TOXIC WASTE.”

So let’s go back to the beginning: RoboCop was born because Neumeier and Miner loved robots and really fucking hated Ronald Reagan.

In the early ’80s Neumeier was a film school graduate working as a story analyst at Columbia Pictures, reading scripts in a trailer on the lot Columbia shared with Warner Brothers. He was captivated by what was going on outside his window. “…Next door was this giant street they built, suddenly, which is a lovely thing to behold in and of itself,” he said in a 2014 interview. “It was for a big science-fiction movie called Blade Runner, and I never had seen anything like it.”

Neumeier marched over to the Blade Runner set to do some work on the film during the night shift, and it was Blade Runner’s replicants that gave him the idea for a robot policeman. The corporate side of the story came from his experience of working at MCA and watching studio execs interact with legendary media mogul Lew Wasserman; Wasserman was the blueprint for “The Old Man” (Daniel O’Herlihy), the chief executive of Omni Consumer Products in RoboCop. Neumeier wanted to skewer the macho, worshipful culture of corporate America in the ’80s. He later said, “Everybody was walking around in the ’80s talking about ‘corporate raiders’ and ‘killers’ and how business was for tough guys. I just thought that was absurd.”

Around the same time, Neumeier made the acquaintance of Miner, who was working as a cinematographer and directing music videos for Bay Area metal bands. They began talking about their projects and discovered that they both loved robot stories as much as they both hated Ronald Reagan. In the 2014 oral history published in Esquire, Miner makes the film’s political and economic intent about as clear as can be: “Because we were in the midst of the Reagan era, I always characterize RoboCop as comic relief for a cynical time. Milton Friedman and the Chicago boys ransacked the world, enabled by Reagan and the CIA.”

Both of them were absolutely determined to keep the movie set in Detroit, because Detroit was the city that best exemplified the politics of the story. Neumeier specifically cites Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist David Halberstam’s 1986 book The Reckoning, which details the decline of the American auto industry, as one of his inspirations while writing. The characterization of Detroit as a crime-ridden hellscape is deliberately mocking the so-called “law and order” politics of the era. As Miner explained it, “That is a cop trope, right? ‘Crime was out of control, blah, blah, blah.’ It’s a very Republican idea.” (The film might be set in Detroit, but it was mostly filmed in Dallas, with a few scenes serving as notable exceptions. Such are the whims of the movie business.)

With that’s ’80s context in mind, RoboCop takes us to a science fictional near future. According to Neumeier, Verhoeven wanted the future to look more like Blade Runner, but producer Jon Davison basically said, ha, no, we can’t afford that. So it’s an unspecified future in which “Old Detroit” is overrun with crime and drugs, and the city’s police department has been privatized and is now run by a mega-corporation called Omni Consumer Products. As the company’s Senior Vice President Dick Jones (Ronny Cox) observes at one of the most iconic board meetings ever put to film, “You see that we’ve gambled in markets traditionally regarded as non-profit. Hospitals. Prisons. Space exploration.”

Jones delivers this line just before introducing his newest innovation: the ED-209, a police robot that he wants to deploy to clean up Old Detroit. Of course, nobody in that boardroom actually cares about crime. They want to empty the city so they can embark on a massive (and massively profitable) real estate development project.

The ED-209 was designed by Phil Tippett, the man behind the AT-AT Imperial Walkers in The Empire Strikes Back (1980), and built by Craig Hayes (credited as Craig Davies). Due to budget limitations, Tippett went completely old school in animating the robot’s motion; he used Ray Harryhausen’s Dynamation technique and filmed it using the older widescreen VistaVision film format. That’s why ED-209 has that halting, janky movement that makes it look so unsettling when it’s first introduced.

Jones instructs doomed junior executive Kinney (Kevin Page) to take a gun and threaten ED-209. We know the demonstration is going to go badly, and it does, in an outrageously over-the-top way. The scene is pure, bloody, pitch-black comedy, with the culminating moment being somebody shouting for a paramedic and the ambitious Bob Morton (played by the wonderful Miguel Ferrer) seizing the moment to pitch his own pet project to the company head.

Morton’s project is RoboCop: an experimental cyborg police officer. First, Morton needs a dead human cop, however—so he has helpfully transferred some officers from less dangerous parts of the city into the worst neighborhood in hopes of getting a fresh donor body. One of those unlucky transfers is Officer Murphy (Peter Weller), an ordinary cop with a wife and kid who just wants to do his job. Murphy and his new partner, Officer Lewis (Nancy Allen), are out on patrol when they get a call about an armed robbery. They chase a group of criminals led by Clarence Boddicker (Kurtwood Smith) to an abandoned steel mill. The criminal gang captures Murphy and tortures him to death in a scene so gruesome the MPAA gave the first several cuts of the film an X rating.

(Those parts, and the climactic scene, were filmed in a defunct Wheeling-Pittsburgh Steel mill in Monessen, Pennsylvania, which has since been demolished. I’ve never watched RoboCop with my dad, who worked for Wheeling Steel at a different mill when he was young, but if I ever do, I’m sure he’ll helpfully identify every part of the mill that he can.)

But Omni Consumer Products isn’t done with Murphy, so he’s brought back to life with his memory wiped and his body replaced by a machine. We see this resurrection from his point of view, with confusing glimpses of memories for which he has no context. There’s a grimly funny moment when the scientists and doctors say they can save his remaining arm, but Morton berates them for caring about preserving the human when they can replace every part with machines.

The RoboCop suit was built by special effects artist Rob Bottin. We’ve talked about his work before in this column; he’s the one who got his start working on the cantina clientele in Star Wars (1977), then went on to craft The Thing in The Thing (1982) and the mutant make-up in Total Recall (1990). That suit was apparently something of a problem for everybody. Verhoeven and Neumeier wanted something more “sensational,” Bottin had to try to make their impossible ideas work, and Weller was miserable the whole time he was wearing the contraption, because it took six and a half hours to put on the face and head prosthetic, and another hour and a half to put on the suit. By all accounts, including their own, Verhoeven and Weller came very close to strangling each other on set, but they also say they made up before it was over.

(Note: There is a lot of information out there about the making of RoboCop, because it was a film that attracted industry interest even while it was in production. The Cinefantastique article from December 1987 is a very detailed contemporary account. As a bonus, that same issue contains a piece wondering if the brand-new show Star Trek: The Next Generation could possibly be any good.)

When Omni Consumer Products debuts its cyborg cop, RoboCop is at first a success for the company, as he struts around the city stopping assaults and robberies. This sequence is punctuated by one of the film’s amazing interludes of evening news clips; news broadcaster Mario Machado and Entertainment Tonight host Leeza Gibbons play the anchors. The news is a litany of apocalyptic horrors, delivered in chipper evening news style, complete with a commercial that shows a family playing the fun new boardgame “Nukem,” in which they try to defeat each other in nuclear warfare.

But RoboCop’s successful patrols don’t last. One of Boddicker’s henchmen (played by Paul McCrane) and Officer Lewis both recognize Murphy, and their recognition triggers confusing memories that send him looking for who he used to be. That leads him to the old Murphy home, now unoccupied and up for sale. He remembers a little about his wife and son as he’s walking around the detritus of their life together, but it’s a distant recognition, the kind of disconnected memories that frustrate him and provide no catharsis.

That’s the scene that convinced Verhoeven to make the movie, even when he was skeptical about the rest of it. It’s the scene he paid attention to when his wife told him he was focusing too much on the outward trappings of the film and not enough on the soul.

I can see why that would draw him in, but I think what’s really interesting about that scene is that it does not lead to Murphy regaining his memories or reuniting with his family or reconciling his past life with his current existence. It doesn’t fix anything. There’s no catharsis. When he talks to Lewis about it later, he says that he can feel the loss of his family, but he can’t actually remember them.

The rest of the movie is a flurry of action: RoboCop discovers that Boddicker is working for Jones, because of course he is; Jones has Boddicker blow up Morton as part of their corporate dick-measuring contest. RoboCop apprehends Boddicker, but he can’t do the same with Jones because he is programmed to keep his hands off the company executives. (That is a very on-the-nose metaphor for law enforcement working to protect wealthy criminals at the expense of everybody else, but it’s one that has only become more relevant over time.)

Jones sends ED-209 and a bunch of cops to kill RoboCop, but he escapes with the help of Officer Lewis. Boddicker and his henchmen track Murphy and Lewis to the abandoned steel mill and there is a big, messy fight. None of the criminals survive that encounter.

And, yes, Rob Bottin also did the toxic waste/melting face special effects on actor Paul McCrane—do you even need to ask? If we all take nothing else away from this film club, let us all cherish our hard-earned ability to recognize Rob Bottin’s special effects when they explode all over the front of cars in a gory mess of fake blood and chicken soup.

From that point onward, it’s relatively straightforward to dispatch Jones. Murphy’s final act in the film is to reclaim his name. Does that make it a happy ending? Not exactly. The world hasn’t changed. The corporation is still in control. The city is still in chaos, violence is still the norm, and rich men are still profiting from it. The company still owns RoboCop. His family is still gone. His tragedy is not undone.

Much like Total Recall, it’s only a happy ending if you don’t think about it. Once you start thinking about it, all the fridge horror returns and you can’t escape how incredibly bleak it is.

Only onscreen, though. Off screen, for the people who made the movie, it was very much a happy ending, because the movie was a wild success. It made a ton of money at the American box office and even more money when it was released internationally on VHS. The character of RoboCop became an indelible part of American pop culture. There are sequels and remakes (I’ve never seen them) and video games (never played them) and comic book appearances (never read them). RoboCop has never gone away.

As for the screenwriters: Neumeier went on to make Starship Troopers (1997) with Verhoeven. Miner also did more screenwriting after RoboCop, but he is now a landscape photographer and writing teacher.

We can’t separate RoboCop from its politics, although people have certainly tried, many in ways that will make you admire their mental gymnastics. A fun and edifying thing to do is to search for what self-proclaimed RoboCop fans say about the movie on Reddit. You may encounter some of the wildest media interpretation known to humankind!

It’s not quite the same situation as They Live (1988), where there is a critical effort to repurpose the film for politics completely counter to the movie itself. It’s more that a great many people who still love RoboCop today saw it when they were quite young, and naturally didn’t pick up on the satire, and aren’t quite sure what to make of the film now.

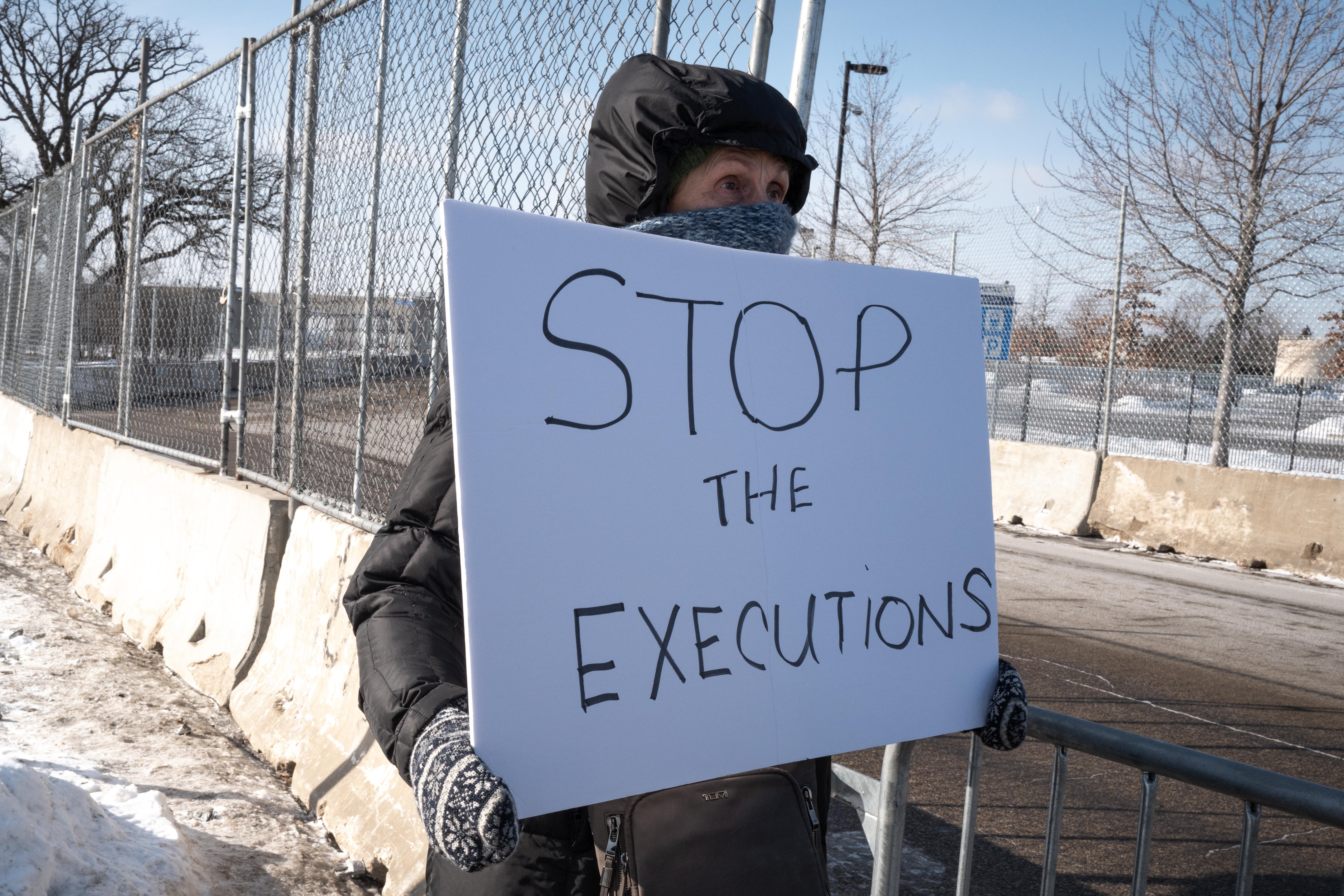

It’s been thirty-nine years and we live in a world in which all the things RoboCop is commenting on are now depressingly normalized: The militarization of police and justification of extrajudicial police violence. The privatization of public services into for-profit industries. The idea that any public-serving part of society should ever be run by people who want to be rich. The fundamental sociopathy of corporate America. The histrionic fear regularly drummed up about crime-ridden urban centers. Rich old men ranting about sending armies into cities to clean them up. None of that ever went anywhere. We don’t need movies to show us government agents shooting people in the streets. It’s on the news right now.

I don’t have a pithy conclusion to this article. I read it over, trying to think of a way to end it, then went up to change the headline. It used to specify “1980s America.” But that’s letting us off the hook too easily.

RoboCop is a great movie. It’s smart and vicious and funny in the darkest, bleakest way. I love it. I’m glad I’ve rewatched it and researched its origins as an adult, with a lot more knowledge and perspective than I ever had as a kid.

But I also wish it hadn’t remained so relevant.

What do you think of RoboCop and its place among the great sci fi political satires to come out of the ’80s? What about the sequels and the more recent remake? There is so more lore about this film… it could fill an entire book, and there is no way I could write about all of it, so I’m sure I’ve left out some interesting tidbits.[end-mark]

You’re Not From Around Here, Are You?

We’ve watched a number of movies about alien invasions, both successful and failed, but what happens when it’s not an invasion? What happens when it’s just an individual or a small group who finds themselves on Earth and now must figure out how to survive? That’s the theme of the films we’re watching in February.

February 4 — Man Facing Southeast (1987), directed by Eliseo Subiela

A man appears in a psychiatric hospital and claims to be from outer space.

Watch: This one isn’t online in many places, but you can watch it for free with English subtitles on Fawesome.tv, and if you do a good old fashioned “full movie” search you’ll find complete uploads around the internet.

February 11 — The Man Who Fell to Earth (1976), directed by Nicolas Roeg

In which an alien played by David Bowie comes to Earth looking for help for his home planet.

Watch: Find links here, including free versions through public libraries on Kanopy and Hoopla.

February 18 — Dead Mountaineer’s Hotel (1979), directed by Grigori Kromanov

A Soviet-era Estonian film about a police inspector encountering some strange guests at a remote hotel.

Watch: You can find it on Cultpix, Klassiki (which offers a free trial), and once again I encourage a “full movie” search of the usual upload sites.

February 25 — Under the Skin (2013), directed by Jonathan Glazer

Either a beautiful alien is hunting men or that’s just what Glasgow nightlife is like sometimes.

The post <i>RoboCop</i>: A Glorious, Scathing Satire of America appeared first on Reactor.